Mostly whimsy and drivel of no consequence. And CHEESE.

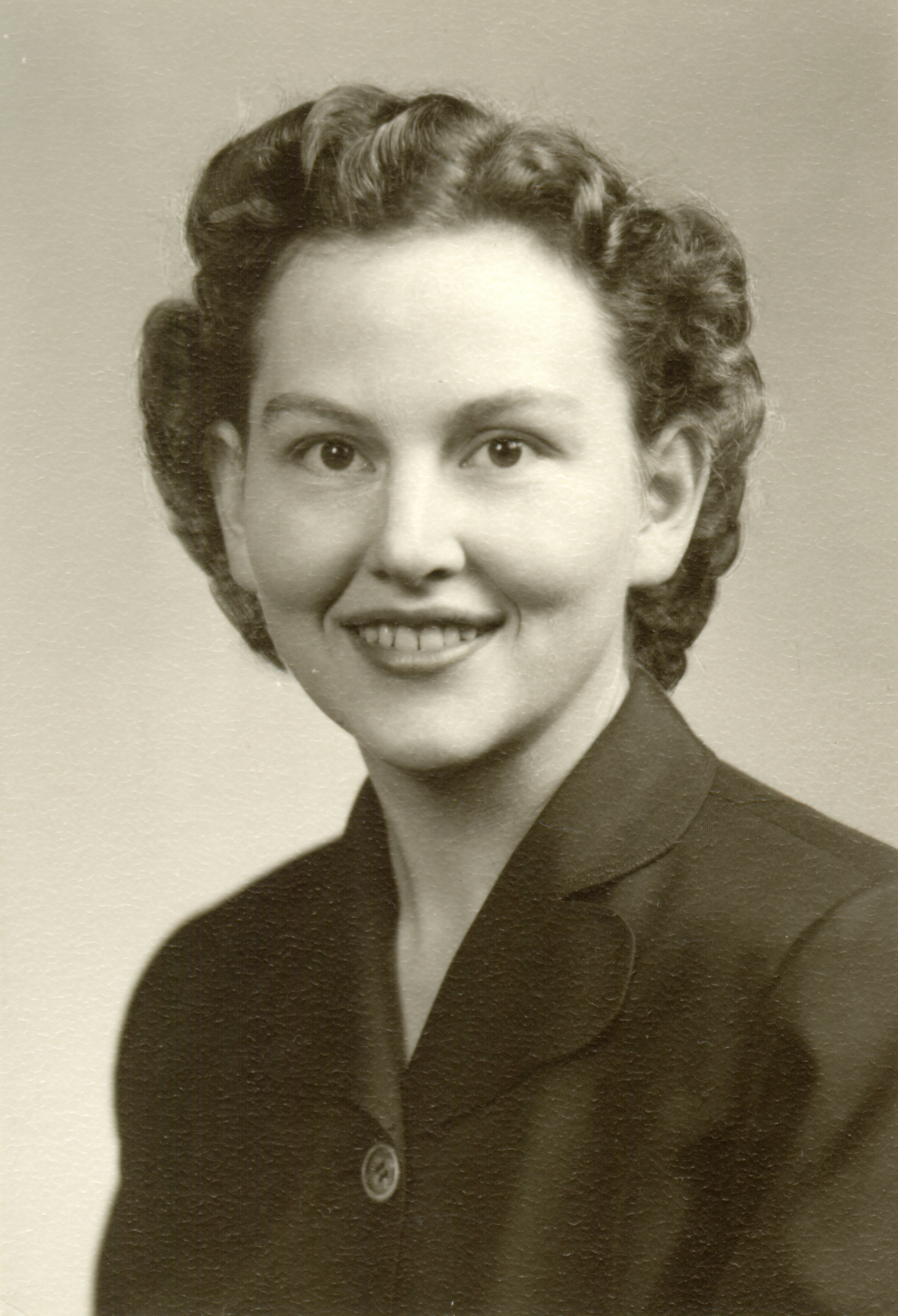

March 5, 1949 was the worst day in my Grandma, Evelyn Monson Lee’s, life. A Chaplain from the Air Force came to tell her that her husband, Charles Shirley Lee, had been killed in a horrible plane crash at Promontory Point along with four other young men. She did not remember that details of that day – or many of them for a while thereafter. We only know these details from her relatives and a letter I recently found from that Chaplain. She was five or six months pregnant with my Uncle Chuck. My Mother was not yet two years old.

After Chuck was born she sat for about a year in her in-law’s garage apartment and rocked her precious baby boy. Then she got up, went back to school, and prepared to take care of her family. The little family lived for years in Bozeman, Montana in the basement apartment of her parents (wonderful people I was privileged to know until they passed away when I was a teenager) while she finished her education. They moved to Provo where she became a Professor as Brigham Young University in Textiles and Clothing. After both children had married and moved out, she eventually bought a condo in Orem in which she lived through her death.

This past year my Grandma faced a battle with colon cancer that prompted her to tell my Mother that it was the “worst thing that had ever happened to her.” My Mom had to remind her about that day, almost sixty years ago, when she became a very young widow.

Because she was a widow, my Grandma was always there for us; she attended every birthday, Christmas and special event she possibly could. When we lived in Stanford (where Janet and I were born), she came to visit, evidently prompting a toddler Kate to walk around after she’d gone home repeating, “Oh dear, oh Dear, OH Dear!” When we, too, lived in Orem, and she was still young enough to tolerate a night on our couch, she stayed over on Christmas Eve. In my memory, her overnight bag was just like the tiny valise the Grace Kelly pulls out in Rear Window. She always had silky pajamas and a satin pillowcase (it influenced me so strongly that I got my first satin pillowcases as a child and now I’ll only sleep on a silk pillowcase). Yes, she was always there for us. And she went to Washington state as often as she could so that she could visit my Uncle Chuck, my Aunt Mary Ellen and my cousins.

I wish we could have been there more for her this past year. My Mom did as much as was humanly possible; she is amazing. I helped as I could. And Grandma was accustomed to being alone and sometimes preferred her solitude. She had always been shy. My Mother said at Grandma’s funeral that she didn’t think she’d ever have married had my Grandpa not inadvertently been “put in her way” when he was a lodger at their house when he was working in Bozeman.

But she was afraid. Her “normal” anxiety was naturally magnified; she was so frightened.

I’ve gone through some of the details from the beginning of her diagnoses, but for now I’ll skip some of the middle. It was pretty horrible for her, and I can’t say that it was easy for those around her. She was living at home, trying to eat and drink enough, trying to…try. But we were concerned. She seemed too weak, but we knew if she was to go into assisted living she’d give up entirely.

She’d decided that she wasn’t going to take any more chemo despite the recurrence of the cancer in her lymph nodes. She couldn’t handle the idea and theoretically her prognosis, even with treatment, was a couple of years. She’d gone to see her oncologist on New Year’s Eve day so that he could give his assessment of a chest CT that was about three weeks old. My Mom said he studied it and studied it. He decided that she’d had pneumonia while at post-surgical rehab (which was very possibly the case). He told me later that he thought he saw some infiltration but it was really hard to say.

We took her back and forth to Christmas Eve and Christmas breakfast and dinner. She saw my beautiful youngest niephew, Bela, blessed (though later we found that perhaps a decline was more ominously at play because she said to my Mom the next day that she thought she’d driven the wrong way down the biggest street on her way to the chapel). She came to New Year’s Eve and she got sweet, tender hugs from a visiting Paisley. She had New Year’s dinner with us. When my Baby Brother was helping her up the stairs she said something about how she couldn’t see.

On Friday, January 2nd, I was supposed to take Grandma to get a transfusion. We all thought that it would help her strength. My Mom was going out of town, but called Grandma that morning before she left and said she sounded fine. I started calling her to see when the appointment was and kept getting no answer. I think on some level I knew something was wrong, but subconsciously perhaps I didn’t want to face the reaction my Grandma had the first time I called the paramedics to come and get her (though she did go) – I don’t know. I finally just showered and went to her condo. And indeed, she was on the floor, attempting to half-sit in a vaguely comfortable position (she had a pinched nerve in her left leg/hip and had pulled tendons as a consequence trying to shift herself). I tried to help her up; she’s lost so much weight this year and I thought I could do it. But I realized that even if I got her up she wasn’t walking anywhere; she’d been on the floor for hours – she couldn’t say how long for certain. I told her I needed to get help and she did not argue with me. I laid her down for a second with a pillow under her head and called 911. Then, because it was more comfortable, I sat on the floor behind her so that she could lean against me as though I were a chair.

In the ER, I saw something I’d never, ever seen before; I saw my always intelligent, well-read Grandmother confused and unable to remember very basic things. I had been in the ER with her when she was in renal failure and she’d been more “with it.” They performed test after test after test, including a chest x-ray, a chest CT, a head CT, ultrasound to rule out a clot, a million blood tests. Nothing to eat or drink (which I didn’t push considering the circumstances). The ER physicians consulted with her oncologist, I told them in private that she’d never been that confused and perhaps it was because she was anemic and had been on the floor for too long – she did need oxygen. I also told them that she denied pain and depression (in the best of circumstances). More time passed. At one point she didn’t know my name. That night, the doctor and the intern came in, said, “Let’s step outside” and then the doctor changed his mind and we stepped into the room with my Grandma.

By some twist of fate, I’d been the one to take Grandma to the appointment with her oncologist during which he told her that “it wasn’t good,” that the cancer had reoccurred in her lymph nodes. That night, the two doctors stood across the bed from me, my Grandma looking frail and tired like I’d never seen. They proceeded to tell me that the cancer had metastasized so fast and so far that it was everywhere. It was distending her abdomen, it had completely infiltrated her lungs and it was all over her brain. They had to admit her, as she certainly couldn’t go home as is. They said that she wasn’t really that anemic, but that she could still have a transfusion and might feel a little better. She was aware enough to sign a DNR form with the admitting doctor who said that Grandma would see Dr. Tudor (her oncologist) in the morning.

My Dad and Baby Brother brought my meds to the hospital. I attempted to sleep on one of those hospital chairs. I tried to make sure that they knew not to pull on her left arm and leg if they could help it. I got a bubbler for her oxygen. I’d made a million phone calls in the ER – my Mom needed to come back from Kansas, she needed to call my Uncle Chuck and my siblings. At five or so in the morning Grandma wanted to sit up. I helped her sit on the edge of the bed. I asked her if she wanted water or a one of those little sponges to wet her mouth. No. Then I remembered what I’d heard was “delicious” (the first time she’d said anything like it in six months) when she was in the hospital dehydrated and starved, her kidneys amazingly coming back from failure: A Popsicle. So I got her a blue Popsicle, prepared just as she liked, broken in half in a Styrofoam cup. She could hardly grasp the stick – she kept dropping it into the cup. But that made her all the more determined to finish it (which she did). They brought her pills (the woman takes hardly any pills, really, as it is – I outdo her in that respect at least five-fold). She HATES pills, but she was determined to take the water herself and do the job. She ended up having her gown and her entire bed changed, which just exhausted her.

Dr. Tudor came to see her. He told me very frankly that the change in the chest CT from three weeks prior to to the one from the night before was pretty horrifying. And as for the brain tumors, she had one on the right side of her head that was pushing hard against her brain/skull; this certainly accounted for some of the confusion and loss of memory, not to mention her rapidly declining strength. He said that she had anywhere from a few days to a week, considering that she wasn’t eating or drinking as of then (and it was not kind to push it at that point, obviously, as her body didn’t want it). He asked if we’d arranged hospice and I told him that my Sister had been trying to schedule a visit so we’d have things in place. Bless Shirleen for having thought of it when she did.

He told Grandma “that it was bad.” This was after he’d walked into the room, told her “You [she] look[ed] terrible” and made her smile. He essentially said, “I know you’re tired and you just want to go home. Let’s get you out of this horrible place.” I’d offered to stay with her; at home twenty-four hour hospice care isn’t a reasonable option in this area. I promised her I’d be there. Between the social worker, Dr. Tudor and Applegate Hospice everything was in place within a few hours. I went to her condo where a hospital bed, oxygen, etc. were delivered. Grandma was transported next. Soon two nurses from hospice arrived. She was home with Lucy, the cat who spent the year in anxious concern for her.

After being carried to the hospital bed, Grandma wanted to sit on the edge of the bed. I got her one of her own housecoats (because hospital gowns SUCK). She drank a little juice. She sat there when the nurses from hospice came to do “intake” and meet her. In the ER, she’d still managed to sign some paperwork herself and even lying on her back and in her confused state her handwriting was so much lovelier than mine it’s just a crime. That day, with a regular pen, she couldn’t put enough pressure on a piece of paper to write. When we got her a pen more like a marker she started to take a “test” they provide to see the state of the patient’s comprehension and ability to follow directions, etc. In the meantime, I signed all her paperwork, including a POLST form. We realized at some point that my Grandma was still laboring away at her sheet of paper. I have never seen such a combination of determination and confusion at work. All of the sudden she decided she was GOING TO WALK. She let one of the nurses support her and we asked her where she was going and she didn’t say. She walked into her living room and sat on her piano bench. The nurses left, and she proceeded to watch, with obvious pleasure, Bela crawling on the floor (she throws a little doll ahead of herself and then goes to fetch it).

It was then obvious that she needed to go back to the bedroom, but when I tried to assist her, she gave me her “talk to the hand” gesture and said, “No, NO.” She has employed this gesture for a number of years when she wants you to stop talking – especially if you’re telling a doctor something she doesn’t want them to know – or she’s offered a treatment or anything not to her liking. And though its meaning has always been very transparently, “TALK TO THE HAND,” she imbued it with what I always felt was a Queen of England flavour. Anyway, I was petrified that she was going to fall. I repeated silently a mantra of “PLEASE don’t fall, PLEASE DON’T FALL.” Anytime I got too near her (though I was in some respects ATTACHED to her as I had her cath bag and her oxygen tubing – twenty-five feet of it – and was desperately trying to keep it from tangling all together or tripping us both) she would say, “No, NO!” My sister-in-law reflected later that it sounded like she wasn’t talking just to me, but to the World; she was protesting the meteoric, horrid theft of her strength. She was losing her ability to move as she wanted. Her dominant hand wouldn’t cooperate. She memory – even her ability to speak were failing her as mere hours passed.

My Uncle arrived that night. She was obviously delighted to see him, but she couldn’t say much. I tried to leave them alone. But he is such a private person, and since she hadn’t much she could say, I thought I’d try to get her to take some of her pills (just the ones I thought might make her more comfortable). I knew if anyone could convince her to do something, it would be him. But she wanted to handle the pills AND the water herself. Let’s just say that it was a debacle and those pills were not ingested. She DID let him cut off her three hospital bracelets which she would not let me do. (I guess the image of me coming at anyone with a pair of silver scissors is always frightening, given my history with sharp objects – especially if your eyesight is rapidly failing – must be a horrific image.)

He left so she could sleep, and Lucy and Grandma and I spent our first night alone. She struggled breathing, some, her wheezing was getting worse. For a number of years now, she’s done what I call, “The Hairball Thing,” when dealing with congestion. As to this…phenomenon, I will not elaborate. And it will be my only “delicate” omission (I couldn’t do it justice anyway). She did sleep some; her snoring was comforting when it came. I already felt so helpless. I didn’t know how we were going to ever get her medicated appropriately. They’d left a kit with meds – strong meds – that were in liquid form. I had mentioned that I didn’t know if we’d get her to take anything by mouth and wondered if there was a way to deliver medication through her Power Port without adding an excess of fluid to her system that would merely prolong the struggling of natural organ shutdown.

The next morning, after another visit from my Baby Brother, my Sister-in-Law and Bela (Bela managed to make her smile when nothing else could) I assisted her in sitting up and getting some water. I brought her more than I had intended (I was trying to get it the correct temperature – not too cold, not hot) and a bendy straw as an afterthought. She insisted on holding the cup. She struggled to get the straw to her mouth, but she insisted on drinking the whole glass of water BY HERSELF. I was hovering on her bed, next to the hospital bed, waiting to catch the cup as needed. Several times I thought it was empty and went to take it away. I received WITHERING looks for that, I can tell you.

My sister, Janet, and her family came from Tooele to visit. Janet asked her how she was and she actually said, “So-so.” It was by far the closest she’d come to admitting that not everything was honky-dory. My Mom arrived. She’d had to get up at 1:00 a.m. to make the flight back. I don’t care how old you are, sometimes the most welcome sight in the World is your Mom.

The days were already becoming a blur. Grandma had some Frosty, which she loved, giving me a deep and abiding respect for the Wendy’s® Frosty. Uncle Chuck came back at some point. Eventually, I went home. It was time for clean clothes (after three days – yes, gross) and a shower and a nap during which I attempted to sleep without keeping one eye and ear at the ready. Evidently she insisted on the entire water routine with my Mother that evening and much less than the amount she’d had earlier took a half an hour or longer to finish.

That night was horrible. I promised myself, when I learned about end-of-life and palliative care at The Division of Medical Ethics, that I’d never, ever let someone I loved suffer because of lack of knowledge or resources. I broke that promise that night. Grandma was having more and more trouble breathing. I’d been gradually increasing her oxygen flow, but the infiltration to her lungs was racing along. She would mumble, “Help me, help me…” and then when I went to her and asked what I could do or asked what was wrong she would say “Nothing.” She also repeated, “I don’t know, I don’t know…” over and over and over again. I finally just told her that it wasn’t her fault. I asked her if I should call the hospice nurses and see what we could do to relieve her anxiety, breathing and pain. She kept saying no. I shouldn’t have asked her. I knew she was mentally altered, and I should have called and used the resources available to at least give her some relief from her anxiety. I have never felt so helpless, even though in retrospect I know I could have and should have called hospice.

I had to do something. I found myself sitting on a footstool next to the hospital bed, with a book of hymns and a tiny blue LED flashlight. I sang anything and everything I thought might be comforting. She was trying to tell me something – pointing vaguely past me. I have no idea what she wanted. She seemed to sleep a little eventually. It was a long, long night.

The next day the hospice social worker called, wanting to meet with me and my Mom. We arranged a time, and I explained how concerned I was about Grandma not being able to take pills and her resistance to pain meds in general. He called her nurse, and she arrived that morning. She got Grandma to take some liquid anti-anxiety medication (with some Frosty as a chaser). We moved her for some reason, and it was patently obvious how much pain she was in, so she took pain meds from the nurse.

The days were definitely becoming a blur. We met with the social worker at some point, the hospice aide arrived; she had an appointment to give Grandma a bed bath on Tuesday. I hadn’t medicated her enough and it was a painful process. She slept Monday night; it was a relief.

My Uncle had to leave. The nurse was there at the time and she and I both thought that Grandma was going to break down, but she didn’t. Each day I was sent home to sleep a little and shower and whatnot. Family came and went. Shirleen brought Will’s tiny poodle to visit, as promised. Ironically, HE was dying (though Grandma was too out of it to know that). She petted him a little, and then she and the tiny white dog slept together for a while.

Tuesday I knew that it would not be much longer. She was receiving the maximum amount of oxygen that the equipment would deliver, yet it still took every single muscle in her abdomen to breathe. My Mom and my Uncle had, at some point during those days, both said goodbye in their ways and gave her permission to “let go.” When I stood next to her I thanked her for her life, for being a wonderful Grandmother; I thanked her for being there. I told her she could rest now, told her she could finally go to Grandpa – anything that seemed right at the time. They say, after all, that a person’s hearing is that last sense to go.

I decided that evening that I would just stay up as long as necessary dosing Grandma with the necessary meds every hour. I didn’t want to hover over her every second – maybe I should have – I could have sat and held her hand. Yet second guessing is too easy. At about 10:30 or so I started up my computer so that I could get some lyrics from a song that’s gone through my mind a lot for the past two years; I just couldn’t remember the first part. The crux of the lyrics is, “May you find your way in peace.” I sang it to her then. I sang with more intent to reach her than I’ve ever mustered in my life. Then I turned on Pie Jesu from the Fauré Requiem. After repeating that a number of times I turned on In Paradisum and let it repeat over and over again.

After 11:30 she had stopped breathing once and then started again. I expected that to go on for a while, so at 11:55 p.m.I walked into the kitchen to get another dose of meds. When I came back my Grandmother was gone. I suppose I heard her last breath, but in a final private act, to the glorious strains of In Paradisum, she slipped away when I was out of the room. I stood with all the syringes in my hands for a minute or so, not knowing if she’d start breathing again. I went and put the medicine back, finally, and checked her pulse. Gone.

I called my Mom. Then I called Hospice. They liaison with the funeral home. A nurse arrived, and with great dignity and care she removed the various tubes. I helped move my Grandma as the nurse cleaned her a little and arranged her in bed. I actually was going to warm the bath wipes in the microwave, as the aide had asked us to do earlier for her bed bath. The nurse and my Mother just looked at me when I said, “It’s 15 seconds, right?” Some things are just too unreal. The nurse disposed of the liquid meds (no morphine or methadone, etc. with which to play, I guess). The funeral home men came and removed her body. My Mom went home.

That was four weeks ago yesterday night. I felt strongly that I couldn’t leave Lucy (the cat) alone. Animals know when something is wrong, so she’d had a very long year, too. I’d been keeping somewhat “normal” hours, but I immediately reverted to my bizarre ever-evolving schedule. I couldn’t just go to sleep. I started to look around with an intent to start sorting things; I thought I might as well be useful.

My Grandma, let’s just say, had a weakness for beautiful things – expensive shoes, LLadro, Waterford, Steuben, more books than a library – and a surfeit of dust. I had to take my brain somewhere else, and it made me laugh and shake my head to find twenty or thirty tubes of Esteé Lauder lipstick here and there and everywhere. I found twenty or thirty Sucrets® tins from various eras – some with actual Sucrets® in them and some with what I can only call miscellany. It made me so proud to see some of the amazing things she’d sewn and worn. It was wonderfully nostalgic to find sweaters that my Great-Grandmother knitted. I’d been forewarned, but finding my Uncle’s umbilical cord still made me squeal.

I don’t know how many days I spent there with Lucy. They came the day after Grandma died and took away the hospital bed and the equipment. Funeral arrangements were underway. I went into her storage unit downstairs to get some framed pictures I’d found on another occasion. I happened upon a box full of love letters that my Grandma had written to my Grandfather when they were engaged and he was away working. In the same box was his funeral program, letter after letter of condolence and the cards that had been attached to pages and pages of floral tributes (according to the notations in his memorial signature book). That was heartbreaking. It took me back to the worst day in her life and wonder again how she survived it all. Here’s an excerpt of the first letter I happened to read, which, under the circumstances resonated profoundly:

March 7, 1946

My Dearest Chuck…

Darling, do you know that 16 weeks from tomorrow you’ll be a married man! The time drags by much too slowly to suit me…

I’m so happy to hear that you enjoy your work so much, dear, and that you are advancing and doing well in it. It is nice that you are taking an active part in Church work too. The young man that you are going to portray in the play must really be quite the character. I would certainly like to be there to see you play the part with your “disarming grin.”

I’m so lonesome for you and I long to see you so very much, darling. I only wish that tomorrow could be the 28th of June. I guess the time will be here before I realize it, though. I love you with all my heart.

I really should go to bed now, dear, so that I’ll be able to get up in the morning. Please be very good and take good care of yourself for me and please write very soon.

All my love, always,

Evelyn

After the funeral, (right before which I slipped a small black, ceramic poodle into my Grandmother’s casket), I slept most of each day, spent part of the wee hours with the computer and hackneyed syndicated television shows. The hours in between I devoured murder mysteries with a fictitious Jane Austen as the heroine (combining two of my Grandmother’s favourite genres: Regency fiction and mysteries). Then I drugged myself to sleep. I’ve been the very portrait of dissolution.

I don’t know what’s been plaguing me more: Broken promises and dwelling on “I should have…” and “I knew better.” Or, in the very throes of self-absorbed thinking – particularly, the idea that I will die alone (oh yes, it’s all about ME). I mentioned this in passing (and tears) to my Mother, who, having plenty to do without indulging my newest self-induced despondency, proceeded to tell me a story about someone who had no children or spouse who had a niephew step up and take care of them as they died. From this I gleaned that the nugget of wisdom that I was to take with me was the following: I must start buttering up my niephews now and figure out who will be the most likely to take pity on me and preserve me from a completely solitary demise.

Another thing that torments my brain is this: NO ONE should ever have to die that way. I don’t mean to disquiet the many people who I know have lost their loved ones in this manner. Yes, it was a blessing that my Grandmother’s death was “fast.” Like I said, I cannot fathom what a prolonged deterioration would have done to her. And because cancer is still a constant and malevolent presence, it is a blessing that healthcare professionals are coming up with an increased awareness of services such as end-of-life care, palliative care and hospice, and the necessity of the improvement of this work. Management of pain is much better than it once was, the stark facts of the process of death are more well-known (thus averting unnecessary treatments that can sometimes even cause pain rather than prevent it), and patients – ideally – are receiving respect and their wishes are honoured when possible.

And I should say right here that I cannot state strongly enough what a godsend the hospice caretakers were for my Grandmother (partly in their support for me and my family – in helping us know what to do); they were incredible. They are angels. I must also express my gratitude for the numerous nurses, aides, technicians and the caring and skilled oncologist who cared for my Grandma. She was so lucky, and by extrapolation, so were we.

BUT, it’s not okay that my Grandmother became a statistic – one of over 560,000 Americans who die each year of preventable cancers. It’s unacceptable that she had to suffer the effects of an insidious and wanton replication of those errant cells. In the end, she lost basic abilities, speech, movement and memory – at first day to day and then hour to hour, and then, it seems, moment to moment. She was SO frustrated. And while we eventually were able to ameliorate some of the effects of the pain, anxiety and trouble breathing, I sat and watched my Grandmother, having had the best care possible, and being afforded the opportunity to be in her own home, struggle with every single muscle to breathe – taxing her already damaged abdomen and lungs. I saw the consequences of her brain tumors as they robbed her of the most basic human capabilities and, I cannot doubt, caused her extreme pain. It is deplorable to know that advanced metastasis in so many cancers, as was hers, drown a person in fluid that collects in a patient’s lungs and other tumors take over their very most basic of actions and thoughts. It’s not right.

Grandma said, not more than two months ago, with only partial facetiousness, that she was going to live until she was 120. She could have approached that goal. She was in such amazing health EXCEPT the cancer. Her strong, kind heart would have kept beating for many, many years. She was robbed and our family was cheated.

But this isn’t all about my soapbox; I will leave most of the intricacies of that for another time. Today, on World Cancer Day, I honour an exceptional life. This is about an anxious and shy young woman who met an extraordinarily handsome, funny, affectionate man who changed her life and would have continued to do so, had he not been stolen from her when they were just getting started. It’s about a woman who did not let this horrible tragedy damage her life beyond repair. It’s about a woman who had the strength to mange her fears so that she could educate herself and provide for a family. It’s about a woman who balanced a career (at a time when it was just not done) with motherhood. This is the story of a woman who was a wonderful mother (and grandmother and great-grandmother). It’s about a woman who was not naturally inclined to social pursuits keeping strong connections with her husband’s family as well as her own so that her children could know about their Father. It’s about a woman, not innately social, who had friendships that extended through many, many years and who respected differences in personality, religion and ideas. This concerns a woman who was still in regular and loving contact with a friend she’d known since she was three or four. It’s about a woman with fine talents who, despite her extremely shy nature, developed and shared those gifts for the gratification of others, and, I hope, herself. It’s about passing the deep love of the the arts and education to her children and, in turn, helping them develop their own talents. This is about a woman with music in her soul who passed that love through her children to her grandchildren who pass it to their children – an endowment of four generations.

I’m still in rather a fog. I’m trying to deal with the loss and the guilt and the sense of unfairness. One of the nights I was there Grandma said, “Don’t leave me alone.” I promised her I would not – I would stay with her – and I did keep that promise to the best of my ability. I hope I was worthy of the task. It was an honour to be with her, in spite of my feelings about the injustice of it all. And if I forgot to say it before, in the mist of those surreal circumstances, I will say it now. Grandma, thank you for always being there. Thank you for being a wonderful grandmother and an amazing person. I miss you every day. Also, I want you to know, that despite the nebulous quality of my convictions and beliefs (or lack thereof), I know that you will be together with Grandpa. It’s not about rationalization (though I am skilled, indeed, in that quarter); I just know it must be so. You’ve waited so long. He’s waited so long. I cannot conceive of it any other way.

I know this is an unforgivably long entry. I was going to cut it. Unfortunately, my brain is just not working that way. So here it ALL is, sprawled out before you. I look at it this way: I’ve not written anything in months, so people can take the next three or four months picking away at this post if they wish.

I’m going to finish with a bit of poetry. I talked about how frustrated and afraid my Grandmother has been during this past year. Still, I found a bookmark on the table next to my Grandmother’s favourite chair – the one she’d been practically living in – with this Dickinson verse on it:

HOPE is a thing with feathers

That perches on the soul,

And sings the tune without the words,

And never stops at all.

Dale

March 26th, 2009 at 12:36 pm

Love, peace, happiness, joy, solace, grace, healing, be with you.

katex

March 26th, 2009 at 5:23 pm

Thank you, Dale!